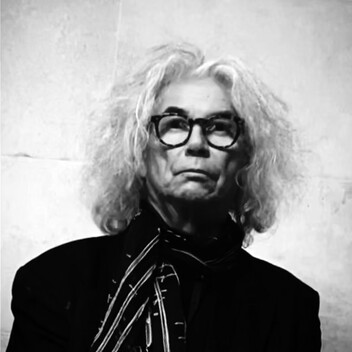

Günter Nest

5 Theses

The paradox of current research and teaching in urban studies.

The results of many so-called inter- and multidisciplinary urban studies and urban development research projects in the last decades reveal bitter paradoxes. Such projects have often merely consisted of a simple juxtaposing of different - but not necessarily equally respected - disciplines, that did not communicate with each other. Additionally, the creativity of architects and artists (if at all involved) was hereby reduced to producing refinements or visualisations for the relationships and phenomena that others – economists, human and social scientists – analysed.

On the one hand, it becomes evident that the much sought after and desired interdisciplinary methods have failed in this era of increasing specialisation. On the other, it can be seen that architecture and art, already on their way towards total commercialization in the face of increasing competition, are being seduced into an uncritical developing of “products”. Lacking instruments with which they could convincingly analyse and especially verbalise today’s social phenomena, architects and artists – far from being imprisoned in ivory towers - are at risk of being unwillingly isolated from current socio-political events and discussions. Yet art in its essence is perhaps the most important field in which present-day cosmopolitan problems as well as relevant theoretical solutions are being recognised, presented and discussed. Is it possible to improve respect for the arts and artists and stenghten their positions within current debates? How can bridges be improved among disciplines that are not communicating enough with each other?

An “urban century” means globalised urbanisation (and a challenge for tomorrow’s urban designers)

The 21st century is on its way to being an urban century: 50% of humanity is already living in urban conglomerations, and soon every second person will be a city resident. Saskia Sassen and others have importantly gotten us started thinking about relationships between “globalisation” and “global cities” – about economically networked cities, whose identities are determined by specifics of production and consumption. Such discussions have further blurred our definitions of “city”, which already was complicated by wildly proliferating definitions. Instead of mourning historical notions of the city we should perhaps search for forward thinking alternatives.

These would consist of new approaches that - with respect to current social phenomena – allow us to effectively act and intervene. Apart from the need for instruments enabling us to adequately observe and describe, this means that planning tools, aesthetic values as well as ethical priorities have to be re-thought. That urbanisation is “globalised” (and not simply “global”) implies that the phenomena characterising it are interlinked and interwoven, transregional and transcultural in nature. To adequately reflect on and deal with the complexity and diversity of these phenomena, we need new perspectives that go beyond a purely economical analysis of cities.City -> Space (this was the meaning of the “spatial turn”, indeed!)

As Jane Jacobs pointed out, cities can live and die. Already in the 1960s the city was proclaimed to be “dead”, at least as it was traditionally understood, i.e. as a place of convergence for differences and with an “urban” public sphere, and

being clearly distinguishable from the countryside. The struggle with city led to searches for alternative paths. By re-orienting the focus from “city” to “space”, it is possible to transcend the limitations associated with the concept of the city as it has been losing clarity and its believed powers of cohesion.

To think in terms of space and spatial relationships also means to go beyond the characteristic 19th century concentration on the primacy of time and on a hierarchy- and period-shaping history. A spatial approach emerges as a viable conceptual alternative, flexible in its consideration of simultaneity, of phenomena and movements in different places, of hybridity and overlapping of differences in a postmodern world. Space is acknowledged as a precondition of social processes, insofar as it constitutes the frame and context of social interactions.

Space cannot be thought of in dichotomous categories

To think spatially and in spatial terms means to engage with a rebellious concept as this is at once abstract/philosophical and concrete/geographic. Furthermore, in recognizing current developments, even the long celebrated differentiation insisted on by urban sociologists (and so many others) between public and private space must be considered to be passé. This polarisation of public and private space recognised streets and city squares for example as a platform for social life and contrasted this with the home as a stage for individual, personal and emotional activity. What, however, is the “publicness” of streets regulated by police and security forces, watched by surveillance cameras and abused by car drivers as their private property? …And what is emotional and “private” about the interior spaces of temporarily used or converted buildings of European downtowns, in which, instead of families, their are workers going about their daily routines? …Is it justified to define as “public” the streets of many mega cities, which illegal vendors occupy and pavement dwellers squat on, or is it not rather to be emphasized that countless thousands of urban dwellers spend their personal, “private” lives in them? …Doesn’t this so-called “public” space, a stage for continuous struggle and conflict with public officials – police and other planning officials generally working to evict the “invaders” – express an extremely emotional atmosphere?Space is a tripartite production process

- “Space is produced, and city is the result of this production process” (Henri Lefebvre)

Following Lefebvre, “space” suggests a collection of interrelated phenomena, whose interactions give shape to city and urbanity. Thus “city” exists in space, and every aspect of social reality develops in space. Understood as a process, “space” is constituted by three specific production processes.

First is the physical production, which speaks to material-technical conditions of cities (buildings, infrastructure, institutions) but also routines of everyday life. Secondly, space is produced as a cultural dimension by mental, or abstract, processes, emerging as religious, ritual and general cultural representations, but also through the activity of planners and architects. Finally, a “social space” takes shape through social practice as a result of everyday practices and human interactions, wherein the potential lies for individual expression. It is important to note that the three fields are simultaneous, essentially interdependent and must be considered as being equally important.

The consequences of this theory are significant for urban researchers as well as practitioners in that an integration is called for of the various aspects of the structuring of daily life, cultural production and human interaction.

- Tactics versus strategies, or: the problem with space strategies

A study of space strategies is necessary in order to critically analyse, (publicly) discuss and intervene in spatial contexts. In line with M. de Certeau, we contrast the concepts of “strategies” and “tactics”. While strategies are typically created by institutions and reflective of power structures, individuals act tactically in order to shape their own space within an environment dominated and defined by strategic practice. Especially urban space is a result of planning and a product of strategic practices. In Lefebvre’s terms, urban space is hence the result of both mental and physical production: of ideological representations that define the routines of daily life, and of daily routines mechanically “reproduced” by urban residents. Yet these inhabitants often move “tactically” through the city rather than according to plan – taking shortcuts and reacting individually to eventual surprises or for example when strolling and window shopping. Such practices are illustrative of the nature of the social production of space, characterised by continuous negotiation, interaction and adaptive processes of socially acting individuals in a social space.

We conclude that a challenge for students in the Space Strategies degree programme is an analysis (also comparative) of urban strategies, and accordingly the development of creative and cooperative “counter-tactics” appropriate to respective cultural, social and political meanings of public acting. Space Strategies students also are expected to develop tactics for creating publicity for spatially relevant issues, and for designing spatial provocations that bring attention to and challenge hidden strategies.

Berlin, 09. Februar 2009,

Günter Nest